Discover more from "Listening to the Essence of Things": musings on life

This morning, migrating geese began arriving from the north in arrow-headed flight, their wings gilded by sunlight as they cried from the skies to warn that summer is ending.

They make me wistful for the years when I lived on a houseboat on the tidal Thames in London, where the geese were my constant companions.

On sleepless nights their rowdy mating consoled me—the lust for life echoing in the night’s dark concert hall. A mother goose built a nest beneath the bench I sat on every morning to drink coffee and watch the birds on the river. She wove in lavender, rosemary and thyme picked from the pots on my deck, downy feathers plucked from her own breast, sticks gathered from the river bank, and brightly coloured plastic wrappers discarded by careless hands. At first she would not let me near, but we reached an agreement. I would not harm her, and she would allow me to sit on my bench atop her nesting bed and share her joy when her brood began to hatch.

She taught me lessons of life during those weeks when we sat together, waiting for her eggs to hatch. With what mock ferocity she tried to scare me away, and with what haughty pride she eventually tolerated my presence. At first I was afraid to go near, but she helped me to conquer my fear. A magpie attacked the nest when she was away gathering more twigs and sprigs. With ageless maternal wisdom honed by sorrow, she cleared away the broken shells and resumed her patient warming of the eggs that were left.

She taught me to let go of my romantic fantasies about nature, when she attacked the newly hatched ducklings in a nest nearby. One by one she broke their necks and left them to float away on the incoming tide, small yellow bodies lost to life. I filmed a savage battle when a swan came too close to her nest. I was sure the swan would drown the goose, but I had under-estimated her perseverance and courage. All this and more were the gifts given by a goose one soft spring not so many years ago.

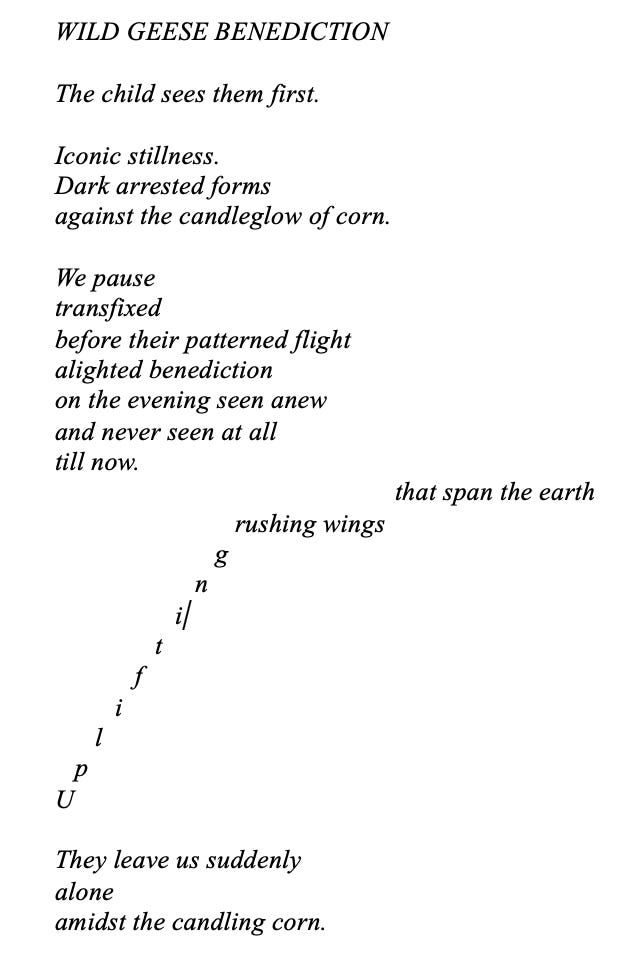

The sound of geese is the sound of memories. Memories of summers that pass more quickly as the years go by. There was a summer walk with a friend when our children were little. We came upon a flock of geese in a field, and the wonder of that sight inspired me to write a poem:

The friend I was walking with no longer counts me as a friend. This is one of the hardest lessons of life—when the precious gift of friendship is shattered by careless conversations and a failure to cherish the other in all her uniqueness and difference. Memories are so often tinged with guilt and regrets.

I’ve been reflecting on what memories are made of. Pictures? Tastes? Smells? Do we see our memories? Can we taste them or smell them? Consciousness is a translucent veil between ourselves and the rest of nature, patterned with memories and imaginings through which we filter the colour, light, touch, tastes, smells, sounds of the world. The swirling kaleidoscope of all that is would dissolve us into itself if we could strip away the screens of thought from the bridal veils of attentiveness. Perhaps that is what it would be like to be a goose—to move through time and space as body/soul at one with the flow of life, made wise with the passing of time—but the blessing and curse of our humanity is to hold the world up before the mirrors of memory and imagination, thought and analysis, to explain what has been, what is, what might be, and what never can be.

What does a memory smell like? I asked myself this when I listened to a conversation between Kirsty Young and Philip Pullman.

The author turned an interview into a dialogue, and the interviewer became the respondent. It was a lesson in how to listen, how to ask, how to care.

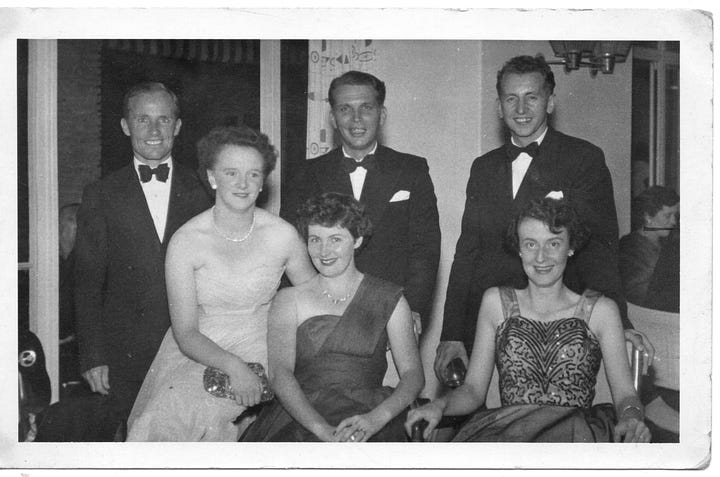

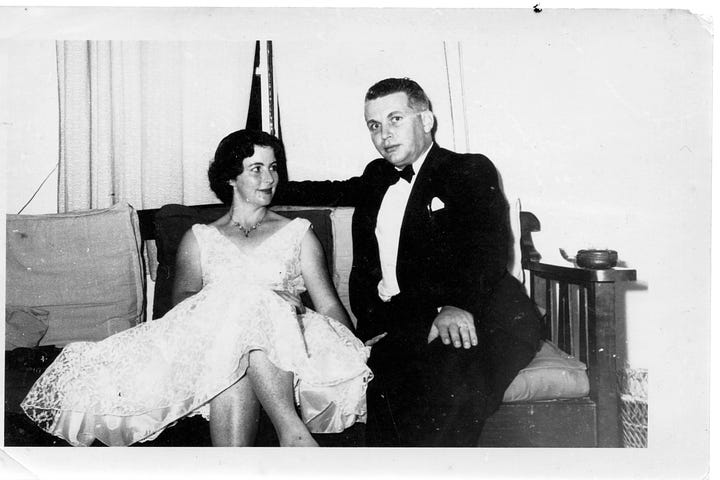

I discovered that I share many childhood memories with Pullman. He spent part of his childhood in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), I grew up in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). We both have memories of sailing between Southampton and Cape Town on Union Castle, stopping off at Madeira on the way, travelling from Cape Town by train, him to Gwelo (now Gweru) and me to Lusaka. Our parents went to the club where white grown-ups went—a glamorous place, said Pullman, that smelled of beer and cigarettes, where children did not go. Our mothers would get dressed up to go to the club.

The photo on the left has a note on the back in my father’s handwriting: “Ridgeway Hotel, Lusaka, 1st December, 1956”. Photos of our dead parents when they were young are perhaps the most poignant of all, but that one on the left has added poignancy. The couple to the right were called David and Jessie Stewart. On 9th August, 1958, a plane en route to London crashed at Benghazi in Libya. Jessie and their infant son were on the plane. They did not survive. David remained a lifelong friend of my parents.

Pullman’s mother wore a perfume called Blue Grass. It would, he said, be a Proustian moment to smell it again. My mother also wore Blue Grass. How could I have forgotten? It was the smell of my childhood, the smell of presence and comfort, the smell that lingered when my sisters and I were left to sleep in the car while our mother and father went to those glamorous places where grown-ups went. Today, that might be seen as neglect, but we loved those nocturnal adventures, snuggled up with blankets in the station wagon with the seats folded down and a supply of snacks to keep us going, while through the windows we could see the distant swirl of their dancing and hear their laughter and music.

The call of the geese that heralds the coming of autumn, the forgetfulness of the smell of Blue Grass, the fading taste of summer like berries on the tongue, the drawing in of darkness as winter creeps over time’s invisible lines. There is never a now that is not also past, never a memory that has not already taken flight into imagination to shape the seasons of the future, arrowing through time like wild geese migrating.

I wonder if you can still buy Blue Grass perfume, and how I would smell it today. Perhaps it’s best left where it belongs—in that distant African past along with the sound of the doves and the screech of the cicadas, the smell of the cracked earth before the rains came, the joy of running out to spin barefoot beneath the first storm, mud squelching between our toes, giddy with the drunken delight of childhood, the taste of ripe mangoes picked from the tree in the garden, mulberries purpling fingertips and lips, cotton poplin frocks wafting fragrance from the kitchen table where the quiet and dignified man we called a houseboy ironed on a blanket covered by a scorched cotton sheet, the sweetness of condensed milk in miniature tins that we bought from the man who came every day ringing his bell and selling sweets from a barrow on the front of his bike (we called him the bicycle boy) …..

The anxious waiting late at night for my father to come home, the smell of whisky mingling with the Blue Grass, the angry voices chasing away the dancing and the laughter, the magpie that comes and raids the nest …

Phillip Pullman talks about the unreliability of memory and the way we make things up in the telling of it. We bring out the things that are memorable and ignore the things that didn’t make much sense to us. I’ve remembered the smell of the whisky but not the Blue Grass. I wonder if I could reverse that. Would the Blue Grass make more sense than the whisky?

The geese cry as they fly—the summer is over, prepare for darkness and loss. Build nests of lavender, rosemary and thyme while there is still time, and patiently wait for the coming of spring.

Feeling sad and angry, reading the news websites (and xitter), I remembered substack and found this - I am so grateful. Finding peace between memory and hope on Sunday morning. Thank you xx

Oh thank you, Tina. I had forgotten Blue Grass, also worn by my mother when I was a child in Leeds. Memories come flooding back…

And how privileged you were to be so intimate with that nesting goose.

Looking forward to the next instalment.